Laura Knight 1877-1970

-

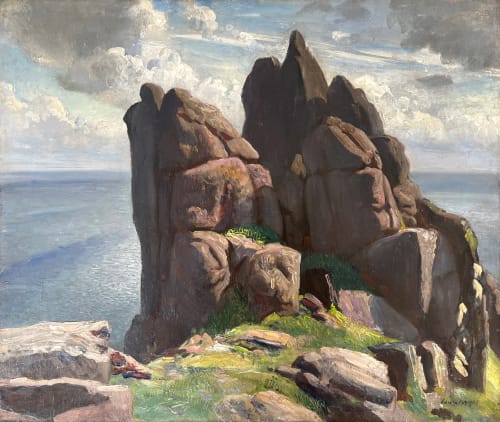

Laura KnightCarn Barges, 1935Oil on canvas63.5 x 76.2cm (25 x 30ins.)

Laura KnightCarn Barges, 1935Oil on canvas63.5 x 76.2cm (25 x 30ins.)

Framed: 81.0 x 93.8cm (31 7/8 x 36 15/16ins.)View full details

Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970) was one of the most significant British artists of the 20th Century, known for her vibrant and empathetic depictions of everyday life. She was also a trailblazer for women in the arts, becoming the first woman elected to full membership of the Royal Academy since its foundation. A key period in her career unfolded in the early 20th Century, when she joined the artist colony at Lamorna, in Cornwall - a place that played a vital role in shaping her artistic vision and legacy.

Laura Johnson was born on 4 August 1877 in Long Eaton, Derbyshire, as the youngest of three daughters to Charles and Charlotte Johnson. Her father abandoned the family shortly after her birth, leaving her mother to raise the children under challenging financial circumstances. Charlotte Johnson, who had briefly attended a Parisian art school, later taught part-time at the Nottingham School of Art. In 1889, at the age of 12, Laura was sent to northern France to live with relatives, who were involved in the lace-making industry. Her mother hoped that this experience would provide Laura with the opportunity to study art at a Parisian atelier. However, Laura found the French schools to be a miserable experience, and the financial difficulties faced by her relatives led to her return to England. There she enrolled at the Nottingham School of Art (now part of Nottingham Trent University) in 1891 at the age of 13, thanks to an art scholarship secured by her mother. At just 13 years and 10 months old, Laura was amongst the youngest students at the institution.

Tragedy struck the family when Laura's mother was diagnosed with cancer in 1892 and passed away in 1893. At the age of just 15, Laura took over her mother's teaching duties at the art school. During her time at Nottingham School of Art, she met Harold Knight, a fellow student, and the two developed a close relationship. In 1903, Laura and Harold married at St Helena’s Church in West Leake, Nottinghamshire.

In 1896, Laura and Harold started to spend their summers in Staithes, a picturesque fishing village in North Yorkshire. There they became part of the Staithes Group, a colony of artists influenced by French Impressionism and en plein air painting. They were inspired by the local community and dramatic surroundings, leading them to make Staithes their permanent home in 1902. The Staithes period was formative for Laura - she honed her skills capturing the essence of everyday life, particularly that of women and children.

At the start of the new century, with the Staithes Group in decline and Cornwall, particularly Newlyn, already established as an artistic hub, the Knights moved to Newlyn in 1907. This period marked a shift in Laura's artistic style, moving from the darker tones of the Staithes Group and the Hague School that influenced that colony, to the brighter palette more typical of her Cornwall-based contemporaries, filled with sunlight and colour.

The Lamorna art colony, situated in the picturesque Lamorna Valley in Cornwall, emerged in the early 20th century as an offshoot of the Newlyn School, drawing artists captivated by the region’s unique light, rugged coastline, and unspoilt natural beauty. In 1908, soon after their arrival in Newlyn Laura and Harold moved to Lamorna driven by a desire for a more serene and inspiring environment. The couple quickly integrated into the thriving artistic circle there that included Alfred Munnings and Samuel John Lamorna Birch (around whom the colony coalesced).

At Lamorna Laura Knight found kindred spirits among other female painters including Elizabeth Forbes, who was a common and very encouraging visitor, Dod Procter, Ella Naper, Ruth Simpson and Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein). The women of the colony, championed by Knight, were not peripheral figures; they were central to its vitality and innovation. Through their art, community engagement, and quiet defiance of societal norms, they helped lay the groundwork for future generations of women in British art. The Lamorna colony offered a progressive environment where these women artists could choose to live independently or in bohemian partnerships that defied Victorian conventions. This relative freedom allowed them to explore themes of femininity and nature without the constraints imposed by the London male-dominated art establishment

The move to Lamorna further allowed Laura to develop her en plein-air painting style, capturing the natural beauty of the Lamorna coast which inspired many of her finest works. It is Knight’s depictions of elegant but modern women atop the cliffs to either side of the cove that are amongst her most celebrated; many in public collections: The Bathing Pool (1913), On the Cliffs (1913, The Cornish Coast 1917 (National Museum Cardiff), A Dark Pool 1908-18 (Laing Art Gallery), Lamorna Cove (1917), At the Edge of the Cliff (1917) and The Green Sea, Lamorna (c. 1917).

In 1913, Laura painted Self Portrait with Nude, a groundbreaking work that depicted herself painting a nude female model. At the time it was considered scandalous for a woman to engage in life drawing, and the Royal Academy rejected the painting. Despite this initial controversy, the painting is now regarded as a highly significant and very beautiful example of 20th Century British Art. It is now part of the national collection and presently has pride of place in the National Portrait Gallery.

Ultimately, Laura Knight's time in Lamorna helped solidify her reputation as a serious and innovative artist. The experience shaped her approach to colour, composition, and subject matter, and helped her to achieve national recognition. Lamorna, in turn, is remembered not only for its natural beauty but also as a formative site in the history of British art—largely thanks to the presence and influence of Laura Knight and her contemporaries.

However, the outbreak of World War I brought challenges. Harold, a conscientious objector, faced local hostility, and the couple's health suffered due to the stress and isolation. In 1919, they decided to leave Cornwall for London, although Laura continued to return to Cornwall for inspiration and to maintain connections with the artistic community .

Beyond the canvas, Knight documented the Lamorna colony in her 1936 autobiography Oil Paint and Grease Paint, offering insights into the personalities and daily lives of the artists there. Her descriptions reveal the camaraderie and creative energy that defined the colony.

During the 1920s, Laura's focus shifted to the world of ballet and theatre. She gained backstage access to Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and painted many of the leading ballet dancers of the time. Her works from this period include The Ballet Shoe and Behind the Scenes in Coulisses. In 1924, she was commissioned to design the costumes for the ballet "Les Roses."

In 1928, Laura won a silver medal in painting at the Amsterdam Summer Olympics for her painting Boxer (1917). The following year, she was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire for her services to art. In 1936, Laura Knight became the first woman to be elected to the Royal Academy, and in 1953, she was elected Senior Royal Academician, the first woman to hold that accolade. Laura and Harold were also the first husband and wife to both be elected Royal Academicians.

During World War II, Laura was appointed an official war artist by the War Artists' Advisory Committee. She completed 17 paintings for the committee, including Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring (1943) and Take Off (1944), both of which are now in the collections of the Imperial War Museum. In 1946, she travelled to Nuremberg to document the war crimes trials, producing a series of arresting sketches and paintings that vividly captured the historic event.

After the war, Laura and Harold continued to live and work in Colwall, Herefordshire. Laura continued to show her work regularly exhibiting every year at the Royal Academy from 1903 until her death in 1970, with the sole exceptions of 1918 and 1922. Laura also exhibited 400 works at the Leicester Galleries and 190 across 40 years at the Royal Watercolour Society. In 1965, a major retrospective of her work was held at the Royal Academy, making her the first woman in its history to be honoured with a retrospective.

Dame Laura Knight passed away on 7 July 1970 at the age of 92. Her work continues to be celebrated for its vivid portrayal of the human condition and its pioneering role in elevating the status of women in the arts. Her legacy lives on through her extensive body of work, which is held in collections around the world, including the National Portrait Gallery, the Imperial War Museum, and the British Council.

Oil Paint and Grease Paint (1936). Laura Knight's first autobiography, detailing her early life and artistic journey.

Magic of a Line (1965). Her second autobiography, offering deeper insights into her experiences and artistic philosophy.

Laura Knight by Janet Dunbar (1975). A comprehensive biography that explores Knight's life and work.

Dame Laura Knight by Caroline Fox (1988). An in-depth look at Knight's contributions to art and her legacy.

Laura Knight – A Life by Barbara C. Morden (2014). A recent biography providing a modern perspective on Knight's life and artistic achievements.

Laura Knight at the Theatre by Timothy Wilcox (2008). An exploration of Knight's works related to the performing arts.

Laura Knight in the Open Air by Elizabeth Knowles (2012). A study of Knight's plein air paintings, showcasing her outdoor scenes.

Laura Knight Portraits by Rosie Broadley (2013). A collection of Knight's portrait works, highlighting her skill in capturing likenesses.

The Graphic Work of Laura Knight by G. Frederick Bolling and Valerie A. Withington (1973). An analysis of Knight's graphic art, including prints and drawings.